MiniMax Conch Video Team Announces First Open‑Source Release: Visual Tokenizer Pre‑training (VTP)

Today, we are excited to introduce Visual Tokenizer Pre‑training (VTP), a new open‑source project from the MiniMax video team. This work explores a critical component of visual generation models—the tokenizer—and its scaling properties within the overall generation system.

The idea might sound unfamiliar: since when does a tokenizer have scaling properties? In the era of large models, scaling is typically discussed in terms of the main model’s parameters, compute, or data size—rarely in relation to the tokenizer.

With VTP, we aim to demonstrate that the tokenizer not only plays a decisive role in the scaling of a generation system, but that the core method for achieving this is built on a simple yet profound insight.

In short, VTP explicitly connects the learnability of latents with general representation learning, thereby positioning the tokenizer as the central player in scaling—for the first time revealing comprehensive scaling curves and expansion pathways. VTP offers a fresh perspective: beyond scaling the main model with more parameters, compute, or data, we can also enhance overall generation performance by scaling the tokenizer itself.

More fundamentally, what we present is not a one‑off “point solution” (pushing a single metric beyond its theoretical limit under constrained conditions), but a performance curve that steadily improves as we invest more parameters, compute, and data into the tokenizer. This means we strive to avoid overfitting to specific scenarios, aiming instead for a method that works robustly in real‑world industrial environments.

Here, we’d like to share our understanding and reflections on this problem from a higher‑level perspective.

01. The Learnability of Latents

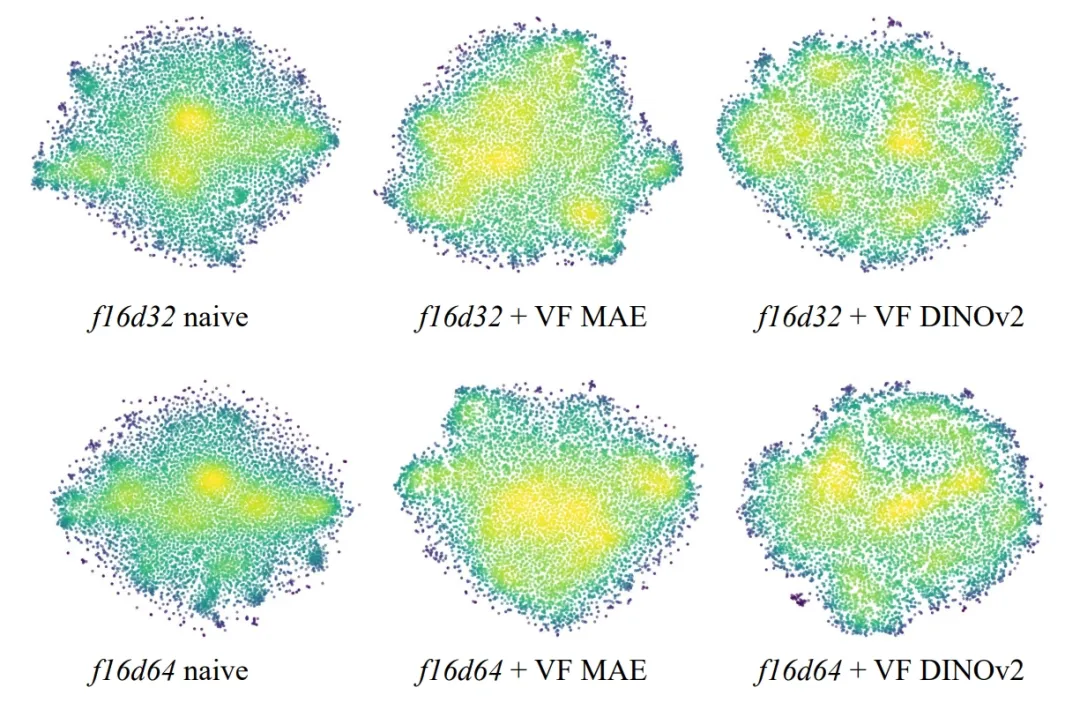

A tokenizer transforms raw images/videos into highly compressed features, typically called latents. In our earlier work VA‑VAE, we introduced a new property of latents: learnability.

This stemmed from our observation that different latents lead to very different downstream generation performance—so the most generation‑friendly latents became our goal. Optimizing for learnability, however, is challenging because mainstream generation systems such as LDM (latent diffusion model) follow a two‑stage design: first the tokenizer maps the raw distribution to latents, then a generative model learns to model those latents. This pipeline cannot be optimized end‑to‑end (we have explored some end‑to‑end ideas, but they remain tricky and won’t be detailed here).

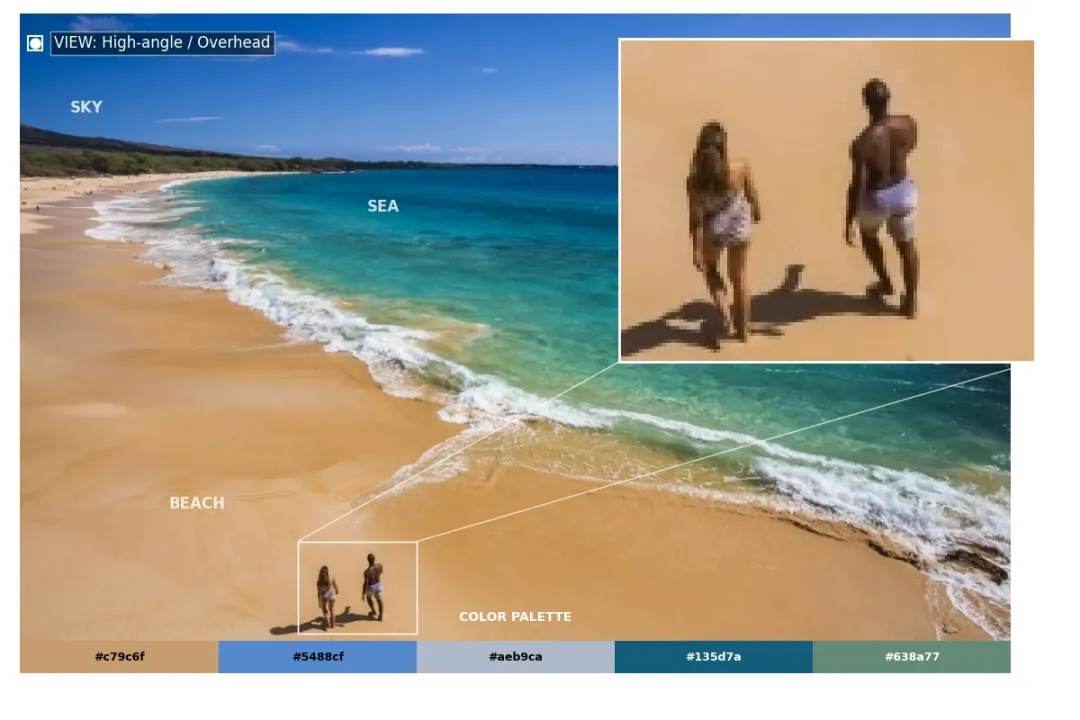

Therefore, we sought a proxy task that can be optimized and that correlates well with learnability, allowing us to indirectly improve learnability. Several representative works have followed this direction, such as VA‑VAE, EQ‑VAE, and SER (the recently open‑source text‑to‑image model FLUX.2 also offers an in‑depth discussion on this topic).

02. From Learnability to General Representation Learning

After introducing the concept of learnability in VA‑VAE, we experimented with many approaches. Looking back, it’s clear that while they helped somewhat, they lacked a fundamental connection. It was perhaps too idealistic to equate learnability with a single, precisely measurable metric (e.g., frequency distribution, uniformity, scale invariance, low‑rank effects). These metrics may correlate with learnability, but they are far from the whole picture.

Gradually, we realized that all these methods were trying to impose some kind of higher‑level “structure” on the latents.

Consider a thought experiment: if a certain set of latents provides a highly structured representation of entities and spatial relationships in an image, then such a structured representation should also be simpler and easier for downstream diffusion modeling—naturally leading to better generation in those aspects.

What, then, is an ideal structured representation? This leads us to general representation learning. We cannot precisely define a perfect structured representation, but we can say that existing general representation‑learning methods show strong adaptability across a wide range of downstream tasks. For example, DINO exhibits excellent generality for low‑level, pixel‑centric tasks, while CLIP delivers strong zero‑shot performance on cross‑modal vision‑language understanding tasks.

This broad applicability to downstream tasks indicates that the latents produced by such methods possess a highly structured representation—one that aligns with human perception. Traditional representation‑learning methods continuously optimize for tasks that humans care about most visually, which is a highly desirable property.

We can even optimistically expect that generation based on such structured latents will yield strong results in aspects relevant to human visual perception. Human visual perception is itself an extremely efficient and intelligent form of compression—closely aligned with the first‑principle definition of an ideal tokenizer.

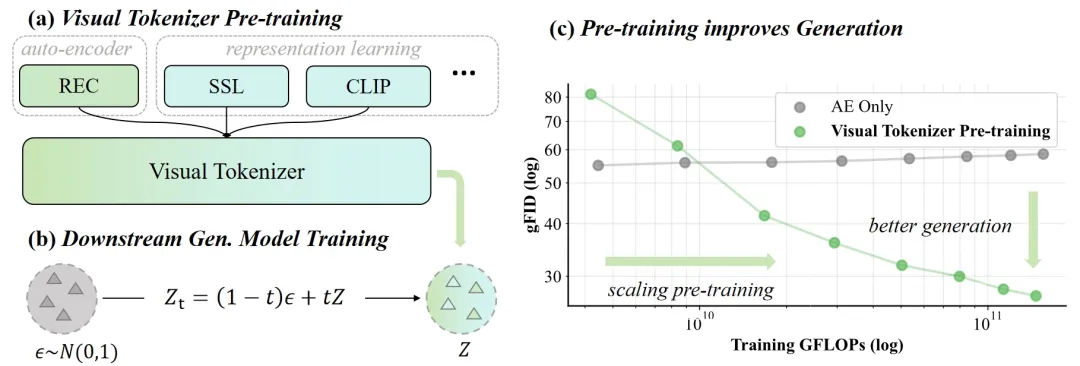

03. Visual Tokenizer Pre‑training (VTP)

By this point, the core solution becomes evident: we should integrate all known effective representation‑learning methods to build a tokenizer.

Some key technical details remain, such as how to view reconstruction (in our perspective, reconstruction is also a form of representation learning, albeit a more basic one), implementation specifics of a ViT‑based tokenizer, and how to effectively jointly train multiple representation‑learning methods. We won’t delve into the details here; those interested can refer directly to the technical report for a more efficient understanding.

We’d also like to share some reflections not included in the technical report. Why didn’t we simply adopt an existing model as the tokenizer, as many works do, and instead chose to pre‑train one from scratch? Two core reasons stand out:

- Representation truly matters, and we want to push it to the extreme. From our perspective, representation encompasses self‑supervision, contrastive learning, and even reconstruction (these are just the more mature known methods; the ideal representation likely includes much more). No publicly available model adequately integrates these approaches, so we needed to train our own.

- A representation‑based tokenizer approach inherently possesses scaling potential, and pre‑training is the most natural way to realize it. Directly distilling or transferring from existing models would complicate the setting too much, undermining scaling properties and limiting our ability to fully validate the approach due to fixed model specifications.

The second point about scaling is the core message VTP aims to convey. Traditional reconstruction‑only visual tokenizers do not scale—whether in terms of parameters, compute, or data. This has been noted in Meta’s ViTok and is rigorously validated in our experiments.

For VTP, by treating the entire downstream generation model training and evaluation as a black‑box assessment system and making the tokenizer the scaling protagonist, we observe—promisingly—that as we increase parameter count, training resources, and data, the downstream black‑box system shows continuous improvement. Given that this black‑box evaluation involves complex generation‑model training, observing scaling under such conditions lends strong support to our conclusion.

VTP also opens up other interesting perspectives. Those familiar with unified understanding‑generation models may recognize that VTP naturally fits into building such unified systems. Unification at the tokenizer level is more fundamental, and we welcome experiments based on VTP.

Data distribution is another promising direction raised by VTP. In principle, the training data distribution of VTP influences how its representations are structured, thereby affecting downstream generation performance. This means it may be possible to optimize the entire generation system by optimizing VTP’s training data distribution—something difficult to achieve with traditional tokenizers.

In summary, the tokenizer, as a key component of generation systems, holds vast room for exploration. Through works like VA‑VAE and VTP, we hope to present fresh perspectives to the community and look forward to seeing new methods and ideas emerge in the field.

0 Comment